The temperature of night

Spall 002: Light, memory, and the infrastructure of feeling

I grew up in a duplex apartment. While short of a bird’s-eye view, the living room window offered just enough elevation that the nearest streetlamp stood nearly level. As such, it occupies an outsized presence in my earliest memories. Fashioned in the “acorn” style common across Toronto from the post-war period through the 1990s, its incandescent bulb cast an almost cinematic white light—just warm enough to ensure that nostalgia came pre-packaged with my first voyeuristic forays to the street below.

It feels, in retrospect, like the nights of my entire youth were set to that light. Brimming with a hint of mist in late June, when humidity thickened the air and I’d scan the yards across the street for signs of life. Blanched and glowing after a first snow, the world turned white on white, as though I’d been placed inside a snow globe. On summer evenings, it served as a kind of curfew beacon, drawing us home from the park in a slow drift. Its tone didn’t just illuminate the night—it textured it.

That texture, of course, was never incidental. The temperature of night is a highly regulated affair in cities the world over. Like a cinematographer choosing film stock, public works departments selected lighting sources ranging from mercury vapor (bluish-white) to metal halide (cooler still) to high-pressure sodium (orange)—each casting its own aesthetic and atmosphere.

The various lighting segments of a city are most clearly visible from space. From 400 kilometres above, the Toronto region resolves into a luminous patchwork—its infrastructure etched in light rather than stone. The outline of the old city still asserts itself, marked by a cooler, more neutral glow, while the surrounding suburbs burn orange with HPS. Concessional grid lines glimmer in east-west bands, while north-south corridors form a finer weave of incandescent thread.

Rail yards and expressways impose their own geometry, while ravines, cemeteries and airports interrupt the pattern with darkness—absences that are legible only because of the light that surrounds them. It is a palimpsest not of text, but of temperature. An archive of decisions made, revised, and layered atop one another across decades, revealed only when seen from a distance.

But not all night was designed from below.

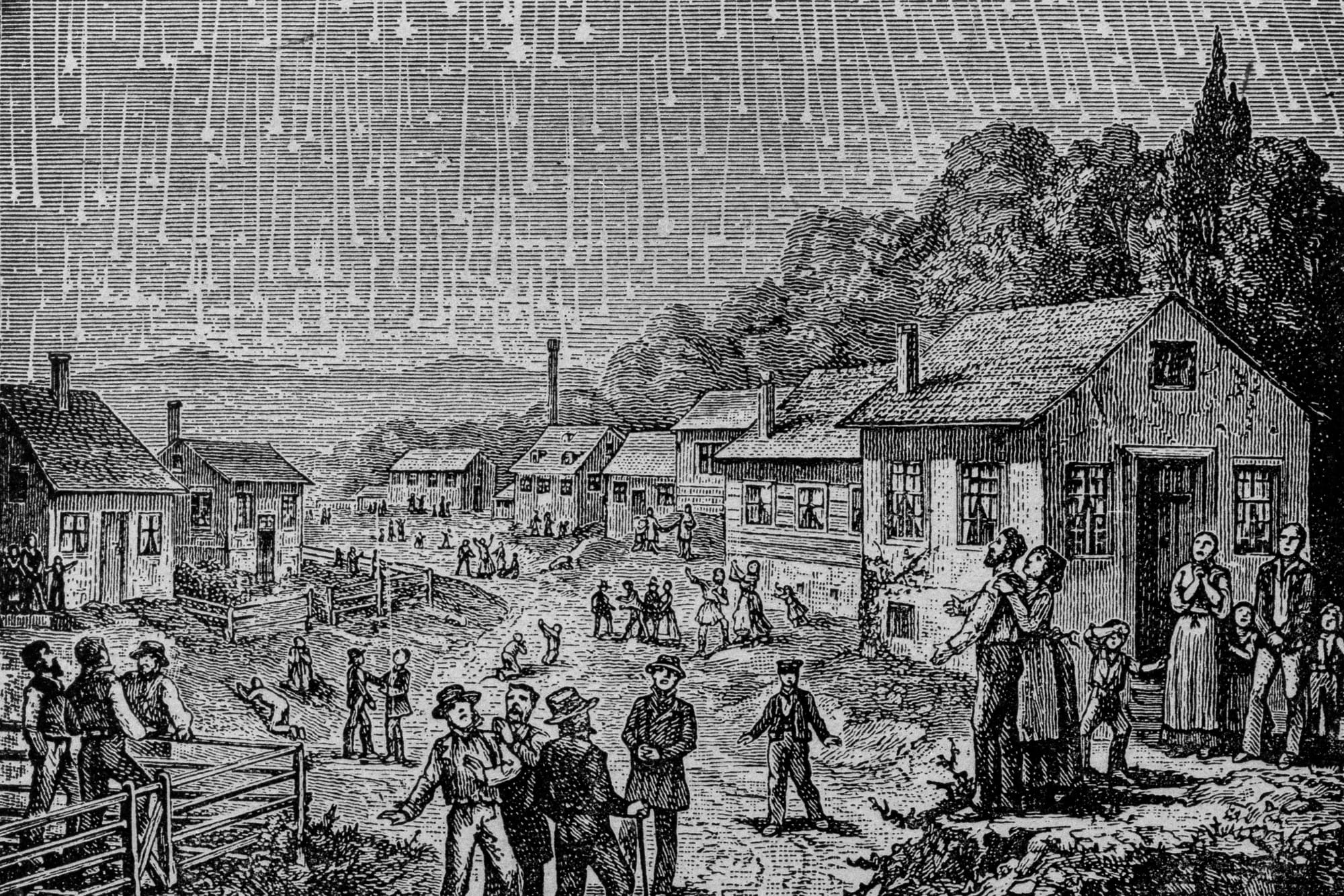

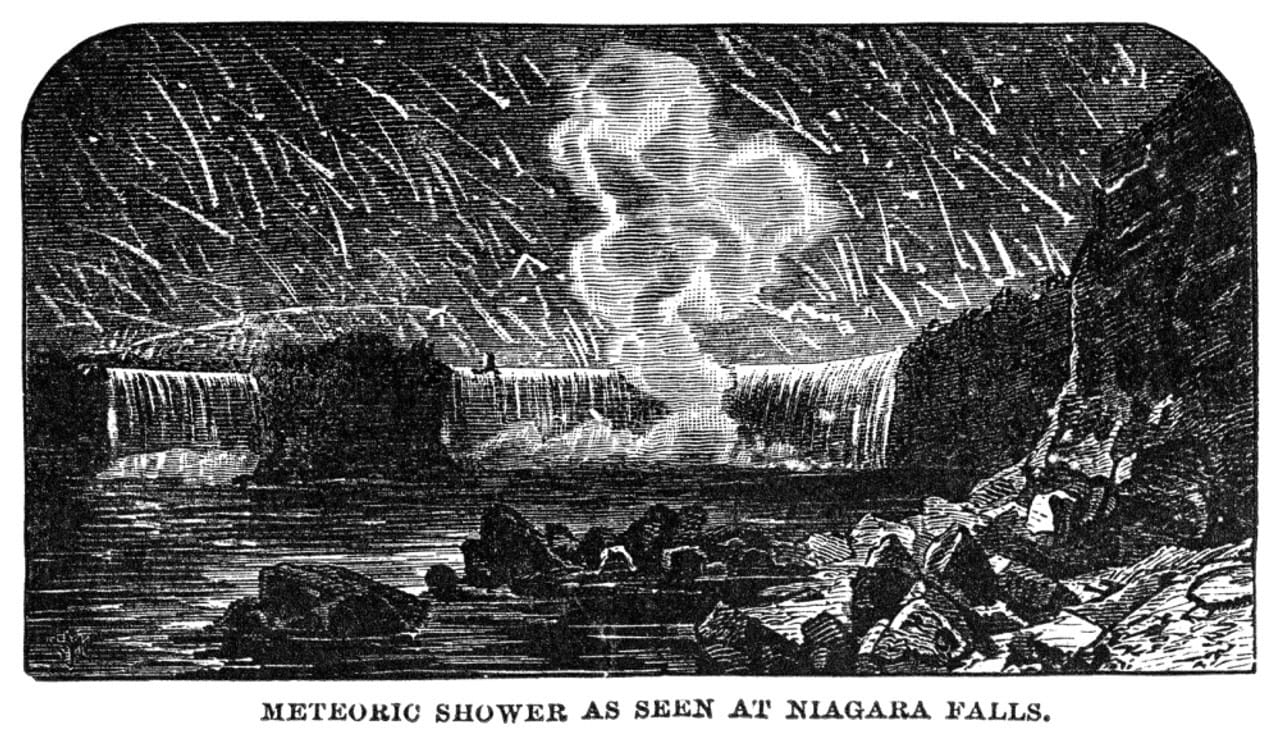

They came in the early hours, unbidden, over the darkened skies of the American South. Sometime after midnight on November 13th, 1833, the heavens began to unravel. What began as a scattered series of streaks, arcs of light barely brighter than a star, soon multiplied, intensified, and refused to stop. Eyewitness accounts from Georgia to Maine describe a sky not peppered but awash with motion: meteors numbering not in dozens or hundreds, but tens of thousands per hour. A deluge of light. A sky turned porous.

The most reliable records speak of complete disorientation. Slaves and farmers, ministers and children, woke to the sound of their animals crying out, or to their bedrooms flooded with sudden light. Some prayed, some ran, many wept. In an era shaped by religious fervour, the response was not one of awe but cataclysm. Diaries from Alabama describe neighbours rushing into the woods, convinced the Last Judgment had arrived. There were those who burned belongings. Others simply watched and waited for the sky to consume the earth.

Newspapers from the following days tried to make sense of it. One editor compared the storm to “the sudden opening of celestial gates,” while another wrote simply: “The stars fell like rain.” In truth, it had been the Leonids—a cyclical meteor shower originating from the debris trail of comet Tempel-Tuttle. But while the astronomical mechanics were later understood, the experiential residue lingered. The spectacle became mythic almost instantly, folded into sermons and seances, local lore and American prophetic tradition. Even now, the 1833 storm is widely regarded as the most intense meteor event in recorded history.

For a single night, they sky itself ceased to behave. What should have been a canvas for quiet, for withdrawal, instead became the stage for a violent and spectacular grammar of light. This was no gradual change, no engineered transition from one bulb type to another. It was a rupture that temporarily rewrote the rules of darkness, and in doing so, revealed just how contingent those rules had always been.

The arrival of gaslight in the nineteenth century redefined the experience of night in cities across Europe. First introduced in Paris in the early 1800s, it quickly spread through London, Berlin, and Vienna, transforming not just visibility but the practice of urban life after dark. Warm, golden, and ambient, gaslight offered a new kind of illumination—less clinical than later technologies, more theatrical than moonlight. It flickered gently, glinted off wet stone, and rendered fog incandescent.

This wasn’t simply a technical upgrade—it was a sensory shift. Streets became softer and stranger. Architecture shimmered with artifice. Shadows lengthened and thickened in corners just beyond reach. The city no longer disappeared with sundown; it acquired new rhythms, new rituals. Gaslight rewrote the rules of nocturnal engagement across Europe, inviting both spectacle and solitude into the night’s domain.

Out of this glow emerged the flâneur—a figure of leisure and observation, drifting through the evening crowd. The city’s new aura made room for detachment, for lingering, for the idle act of looking. Under gaslight, urban life didn’t just continue after dark. It became defined by it.

But, for all its glow, the age of gaslight was a brief flickering chapter in the long night of the city. In a matter of decades, the warmth and shimmer of that nocturnal world gave way to something cooler, sharper, more electric. The temperature of night shifted again—this time not with softness, but with voltage. Neon, an inert element born in stars and buried deep within the Earth, was extracted, purified, and sealed into tubes. When electrified, it glowed with an otherworldly pulse—an alchemy of atmosphere and current that rewrote the city’s nighttime register in synthetic colour.

If gaslight softened the city, neon sharpened it. Where the former glowed with the warmth of hearth and flicker, the latter pulsed—synthetic, brazen, and unmistakably modern. First introduced in Paris in 1910, neon quickly spilled across the Atlantic, where it found its fullest expression in the American city. It was no longer about safety or visibility. Neon was a calling card, a lure. It didn’t just illuminate—it seduced.

The alphabet of the night changed. Letters no longer hung discreetly above doorways. They shimmered in reds and greens, traced in argon and mercury vapour, wrapped in glass and voltage. The language of the city grew louder. Light became movement. Logos danced. Arrows blinked. The outlines of cocktails, palm trees, or women’s legs flickered with insistent rhythm. The city no longer slept—it advertised.

But beneath that voltage was something rawer. Neon lit not just nightclubs and cinemas but peep shows, burlesques, and after-hours bars. It marked the theatres of temptation and transaction. The red-light district—named not metaphorically but literally—was organized by the chromatic cues of capital and sex. Light shaped desire, but also risk. It signalled a kind of sanctioned deviance: pleasures to be purchased, bodies available for trade, shadows just outside the line of vision. If gaslight invited the flâneur to drift, neon drew him in with a grin and a price tag.

This was not the curated warmth of the incandescent bulb. Neon offered the night as marketplace and maze. It was ambient in the loudest possible sense—making every block feel like a threshold, every intersection like a dare. By mid-century, the temperature of night had become more than physical. It was a measure of appetite.

When the lights went out on the afternoon of August 14, 2003, most people thought it was a little blip. I had just finished moving apartments and was paying the bill for lunch when the credit card system went down. Unfussed, the server reached under the bar and produced a credit card imprinter—one of those metal clunkers, a “knuckle buster” relic of the 1980s I thought had been formally retired.

Back at my new apartment, I climbed onto the roof and looked south along Yonge Street, all the way to the lake. What I saw was odd: a slow, thick exodus of people walking north. At the time, the scale of the outage was unclear, but this was the first sign that it wasn’t one of the rolling blackouts that occasionally posed an inconvenience. At first, there was confusion. And then, something close to grace. Random citizens stepped into intersections to direct traffic. Shopkeepers pulled their inventory onto the street. Ice cream parlours held impromptu clearance sales, handing out melting stock to strangers in line.

By sundown, the city erupted in communal activity. Restaurants glowed with candlelight, not marketing ambiance but by necessity. Conversations broke out between neighbours. Entire blocks gathered in the street, liberated from schedules, screens, and the logic of productivity. The night air was thick with something else—a kind of ambient intimacy, uncoordinated and rare. In the absence of power, the city became self-aware.

Beyond exposing the vulnerabilities of the power system, the blackout offered something more unexpected: a reset. It began with a single failure—an overloaded line sagging into foliage in northern Ohio—but that fault rippled outward. Alarms failed, redundancies faltered, and within minutes, the grid began shedding load across multiple states and provinces in an attempt to protect itself. Like tectonic stress long buried in the crust, the pressure had been accumulating invisibly, until the system gave way.

For a brief window, the temperature of night was ungoverned by infrastructure. It returned to something elemental—pools of candlelight, the sweep of car headlights, the jitter of flashlights against alley walls. In those hours, the affected cities slipped into an older rhythm, and people—freed from the backlit script of schedules and devices—moved differently. Night, for a fleeting moment, did not feel engineered.

The blackout was not the event itself, but its residue. A fracture that revealed the structure beneath. Spall, in this case, wasn’t physical—it was ambient, behavioural, temporal. The grid, usually so seamless it escapes notice, had failed. And in its failure, it became legible. Like all spall, the blackout reframed what had seemed whole, illuminating not just the night but the systems that define our experience of it.

If the city is a text, then night reveals its marginalia. Each glow and absence, each hum of neon or flicker of flame, each engineered temperature of light and darkness, is a kind of annotation—layered, contested, half-erased. We navigate by these traces without always knowing it. But once seen, they linger. A light source replaced. A corner forever changed.

The night remembers what the day forgets.