First, there were fractures

Spall 001: A brief genealogy of extraction and accumulation

In the mining regions of 17th-century Saxony, where timbered adits webbed the hillsides and extraction was measured by mule-load, a new entry begins to appear in the margins of guild records and yield ledgers: “spall.” It was not a commodity nor even an object of concern—just a notation of what came loose.

Gunpowder had recently entered the trade, a technological intrusion adapted from military use. Before that, rock was broken by fire-setting and hand chisels, coaxed into parting by heat, water, and repetition. Powder altered the method and the material at once. The seams fractured more unpredictably. More force meant more yield, but also more waste. Explosives created fragments that could not be shaped, only cleared. These were the spalls.

They marked a shift not just in technique, but in temporality: from endurance to velocity, from coaxing to breaching. Spall referred to what broke off under pressure—not as failure, but as by-product. The term settled into use without ceremony. It was not named into existence so much as swept aside.

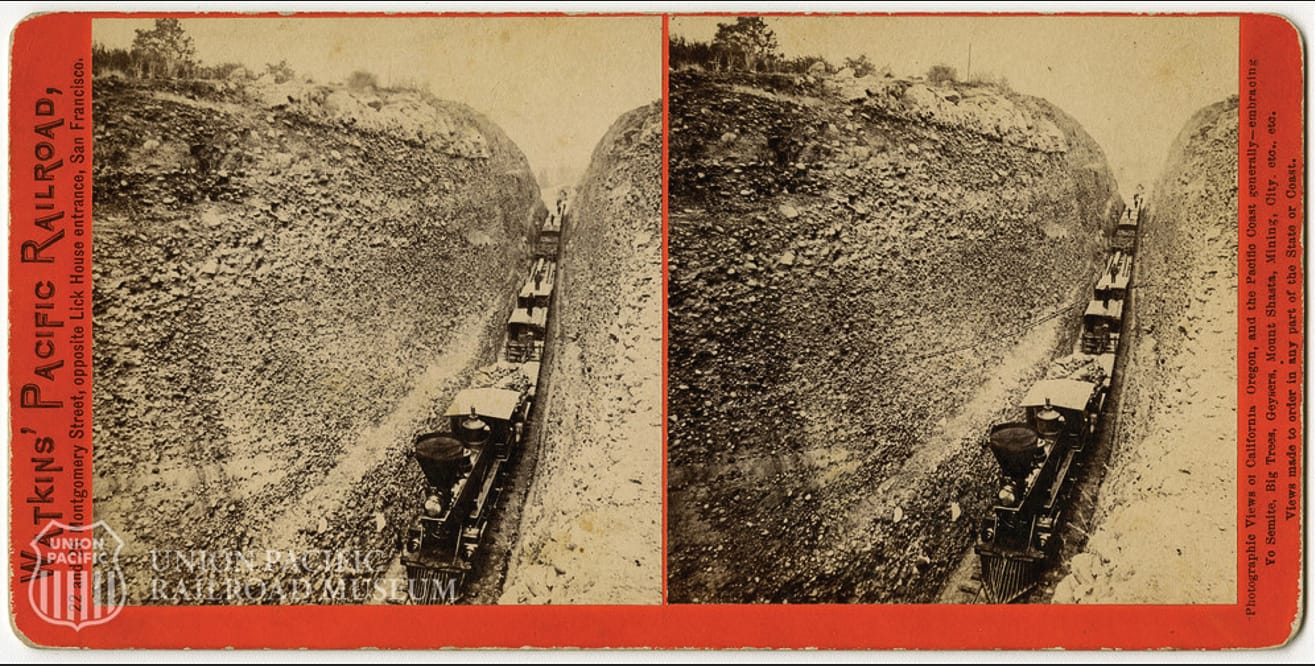

Fast forward to the mid-19th century, and vast accumulations of spall were quietly marking the edges of empire. The construction of the North American railway—an infrastructural fever dream of steel, ties, and blasted stone—generated millions of tons of fractured rock. To lay track across mountains and prairies, crews drilled and packed charges into granite faces, detonating their way forward through what seemed immovable.

The pace of expansion demanded rupture. In the American West, during the gold rush years, whole hillsides were flayed open in search of veins, leaving talus slopes and scree fields that had never existed before. Mining towns rose amid their own rubble. In both cases, spall became a new sort of geography—an emergent terrain of extraction, forming beneath the feet of workers and settlers alike, even if it went mostly unnoticed.

Not all spall is born of dynamite or design. Some is shaped by slower, more ambient force—the exfoliation of granite in desert heat, or the rhythmic freeze and thaw of alpine stone. Erosion does not announce itself. It accumulates until a fragment loosens, and what had seemed whole becomes visibly stratified. What breaks off was always coming apart. The structure only appeared to hold—until it didn’t.

Spall is thus both what breaks off and what it reveals. A fragment, yes—but one that makes visible the strain that preceded it. The fault lines build, often in silence, as pressure accumulates before rupture becomes a kind of testimony.

Spall is not strictly what the event leaves behind—it's what gives the event its shape. The fragment doesn’t follow the rupture. It is the rupture. The instant something breaks, there is spall: material sheared from the whole, neither fully part of it nor fully outside.

There’s a temporal slippage in the term. What flakes away appears after the fact, but its presence retroactively alters what came before. Even as we are surrounded by the posture of stability, the appearance of a crack recasts that posture as illusion. So while the accumulation of spall can be used to mark time, its existence also suggests that pristine objects and the scenes in which we view them carry within them their future ruins.

Spall unsettles the trudge of linearity. What comes loose does so in a moment, but it points backward—to forces long in motion—and forward, to the unravelling yet to come. It is the first visible sign that the whole was never whole.

Some fractures are too large to ignore. Others slip by unnoticed. But every fragment that breaks free—even the smallest—alters what surrounds it. A chipped edge, a fissure in the grain, a seam that opens under stress: none of them reset the clock, but they reframe the time that came before. What looked solid becomes contingent, the visible index of a system strained beyond its threshold.

And so, the ledger: an accumulation of fragments that orient us. No thesis, no centre. Just pressure and release. A record kept in pieces. Each entry a surface pulled back, a point of exposure, a glimpse of what the system can’t fully conceal.

Sometimes it’s memory, sometimes it’s infrastructure. A quiet seam in an urban expressway, fretting loose. Concrete flaking away to reveal rusted steel beneath. Repairs done in patches. The surface holding, barely. But what’s visible now won’t un-see itself. The fracture has begun to speak.

And once it does, it calls for a different kind of attention.